A real sensation awaited the audience of Caroline de Guitaut's lecture at the Faberge Museum last Saturday. For the first time, the senior curator of the British Royal Collection publicly announced that she had discovered the surprise of the eighth egg of the Imperial Easter series, which had long been considered lost forever.

Caroline de Guiteau's lecture was dedicated to Russian stone carving art in the Royal Collection of Great Britain. The British Royal Collection is the largest European collection that has come down to us unchanged. Today it has more than a million different objects of fine and decorative arts. The collection is under the protection of the monarch, but is not his property as a private person. It is especially valuable that all the objects are, in fact, presented in their historical context: they are exhibited in thirteen palaces throughout the UK.

A significant part of the collection consists of paintings, books, objects of jewelry and stone-cutting art created by artists from Russia. Their appearance in the collection is mainly due to the political and dynastic relations between the two countries, but many items were simply purchased by monarchs, who are great fans of the work of Russian masters.

The World's Fair in London in 1851 contributed to a sharp surge of interest in Russian stone-cutting art. Wealthy representatives of the English aristocracy began to increasingly purchase vases, candelabras and other interior items made at the lapidary factories of Peterhof, Yekaterinburg and Kolyvan. There are real masterpieces in the British royal Collection, for example, a huge vase kept in the Hermitage and presented by Nicholas I to Queen Victoria as a sign of gratitude for the warm welcome extended in London to his son, the future Emperor Alexander II.

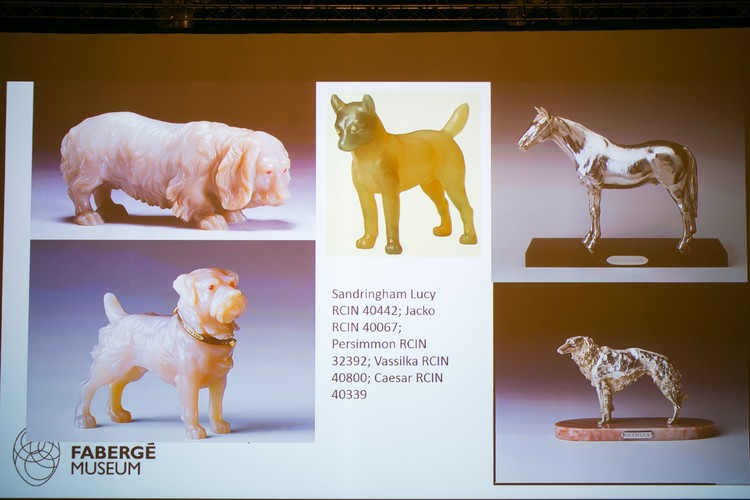

Caroline de Guitaut also showed images of many other objects from the unique collection, including floral sketches made in Faberge workshops and gift boxes made of jasper, jade, turquoise and rock crystal. “Even the most sophisticated expert in them is still amazed by the phenomenal subtlety of the work,” said Ms. de Guitaut.

But the audience that evening was struck by a truly sensational discovery, which Madame de Guitaut announced very modestly: "At this conference, I heard a lot of new interesting facts, and I decided to share information that might be interesting to my colleagues, too." It turned out that Caroline de Guiteau recently discovered a surprise of the eighth egg of the Imperial Easter series, which until now was considered lost.

The eighth egg of the Imperial series "Diamond Grid" was ordered by Alexander III as a gift to his wife, Empress Maria Feodorovna, for Easter 1892. The eggshell was carved from a translucent apple-green stone with rose-cut diamonds inlaid in the case. Initially, the egg had a silver or gold stand with cherubs. It is believed that they symbolized the three sons of the imperial couple: Nicholas, Michael and George. It is also known that there was a surprise inside the egg: a small elephant with a plant. His description remained in Faberge's account books and was translated into English by Tatiana Faberge and Valentin Skurlov. During the revolution, the egg was confiscated, and a few years later it was sold abroad. Having been in several private collections, today it is in the collection of the McFerrin family in the USA. However, the surprise of this masterpiece has disappeared without a trace.

"Some time ago, I was preparing a new catalog of the collection and discovered a small elephant figurine in the funds," Caroline de Guiteau said with excitement. – "I remembered the description of the surprise well and suddenly the thought came to my mind: what if this is the elephant?". After rereading the archival description, Madame de Guitaut was even more convinced of the correctness of her guess. Another fact spoke in favor of the hypothesis: Empress Maria Feodorovna was born in Denmark, where the knightly Order of the Elephant was founded by King Knud IV in the 16th century. The elephant depicted on its emblem, symbolizing purity of thought and protection of the Christian faith, was almost identical to the surprise.

However, in order to present such a hypothesis to the scientific world, it was necessary to find more serious grounds, but the search for documents that could shed light on this mystery did not yield anything. It became clear that there was no other way out but to work with the subject itself. With great excitement, a group of restorers led by a watchmaker from the British Royal Collection dismantled the elephant figurine.

Its mechanism was very similar to that of another elephant from the collection. After the restoration of the lost parts, the elephant was reassembled. "It is simply impossible to describe our emotions when the wind-up key fitted perfectly to the mechanism and the elephant went, began to move his legs, shake his head, perhaps for the first time in the last 80 years!"

However, a fragment of the elephant's turret was lost. Apparently, it simply fell away due to metal fatigue. But there was an opportunity to look into the base of the figure: it was lined with red felt. "For a long time I could not understand why the material was placed there. After all, no one will look inside the clockwork figurine. But then it suddenly dawned on me: it could have been a lid. When we took off the top of the turret, my heart almost stopped: there was a brand of Faberge. The proof we've been looking for for so long! And then there was no doubt that this was the elephant."

Ms. de Guitaut noted that there is still another mystery in this story: how did the figurine end up in the British Royal Collection? Most likely, it was acquired in 1935 by King George V, but it seems that then no one could have suspected what value it represents not only for art, but also for history.

Caroline de Guitaut stressed that she decided to publicly announce her discovery for the first time at the conference at the Faberge Museum in St. Petersburg, since today the Faberge Museum has become a key platform for professional communication of international specialists in the field of decorative and applied arts.